Gastrointestinal endoscopy began with the introduction of the gastroscope, which prompted active clinical use of endoscopes in subsequent years, and thereafter various fiberscopes were also applied clinically. In 1984, electronic videoendoscopes were also developed. Unlike fiberscopes, which directly detect light signals, electronic videoendoscopes convert electronic signals into images via semiconductor elements and allow various forms of electronic image processing and analysis.

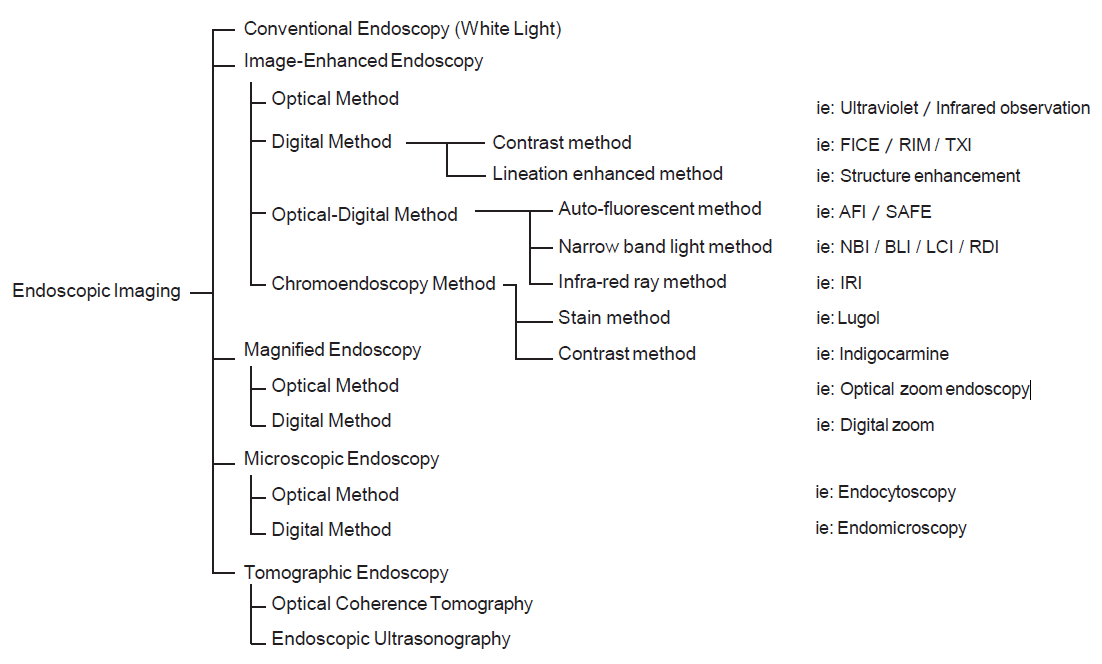

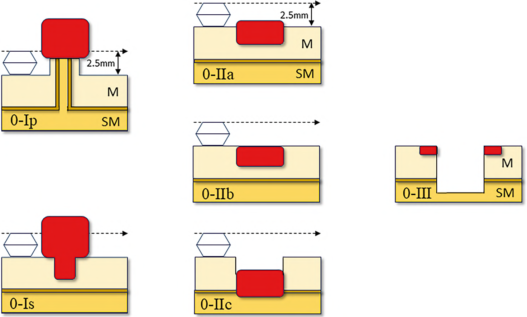

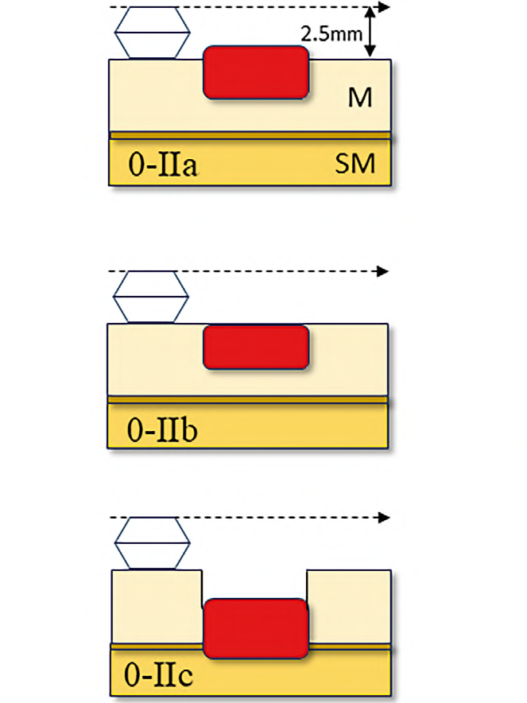

Between the late 1980s and early 1990s, research on image processing and analysis was conducted mainly by the National Cancer Center Hospital East and Olympus Group, which led to basic experiments on narrow band light imaging starting in 1994. As a result, a patent application was made in 1999, and a narrow band imaging (NBI) device (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan) was introduced commercially in 2006. Since the early 2000s, it has been demonstrated by a number of researchers that NBI is useful for early diagnosis of cancers of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, esophagus, stomach, and large intestine. A succession of similar techniques was later made public, and interpretation of the term “special light observation” began to differ among academic societies and research organizations. In view of this problem and the need to establish internationally applicable terminology for endoscopy, we proposed an object-oriented classification for endoscopic imaging in 2008. Basically, the concept was that endoscopic imaging can be divided into five categories: (1) conventional endoscopy (white light endoscopy (WLE)), (2) image-enhanced endoscopy (IEE), (3) magnified endoscopy, (4) microscopic endoscopy, and (5) tomographic endoscopy [1].

IEE is subdivided into optical, digital, optical-digital, and chromoendoscopy methods.

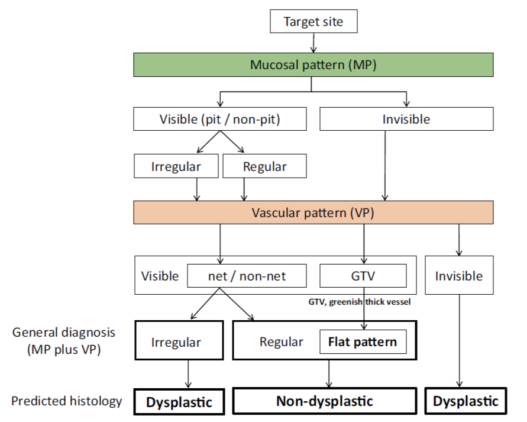

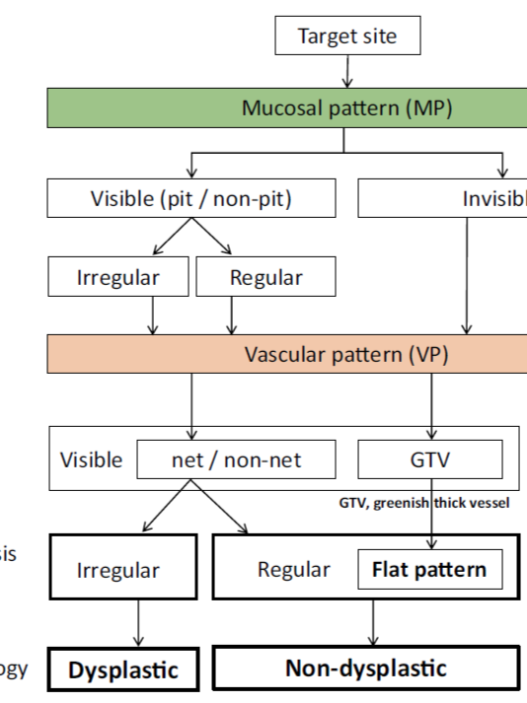

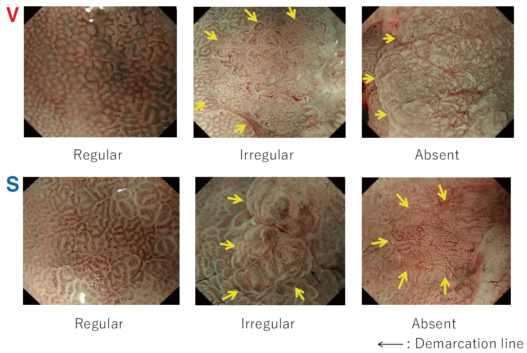

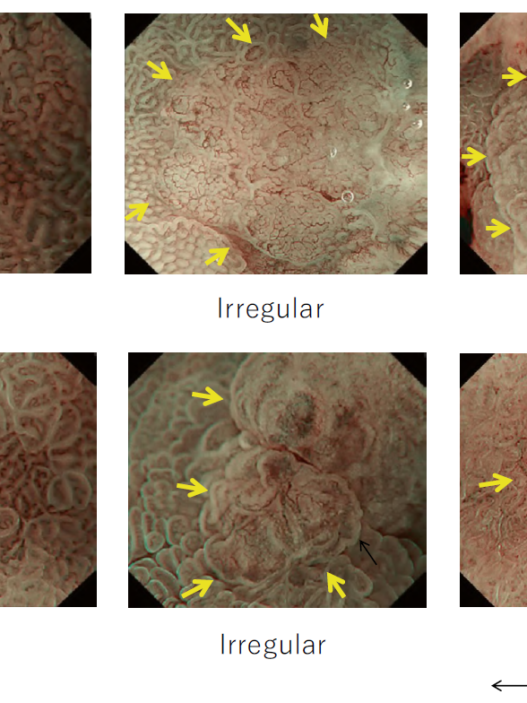

While NBI has spread and contributed to the standardization of diagnosis on a global level, our colleagues have worked tirelessly to further improve the quality of endoscopy. Over the last 15 years, owing to the development and worldwide spread of NBI, international classifications have been introduced in the field of gastric cancer, Barrett’s esophagus, and colorectal neoplasia.

Since the introduction of this classification, several IEE techniques have become commercially available through advances in endoscopy technology, including blue light imaging (BLI), linked color imaging (LCI), red dichromatic imaging (RDI), and texture and color enhancement imaging (TXI). Therefore, a revised version including those techniques is presented in Fig. 1.

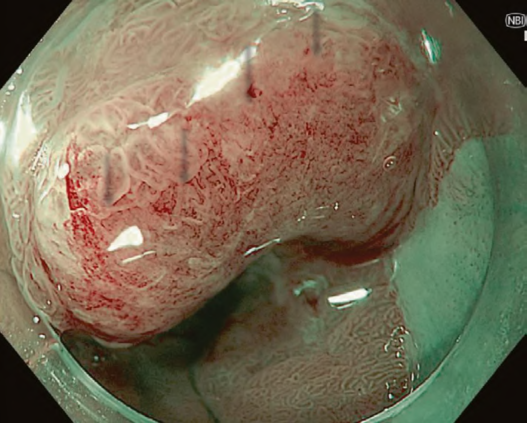

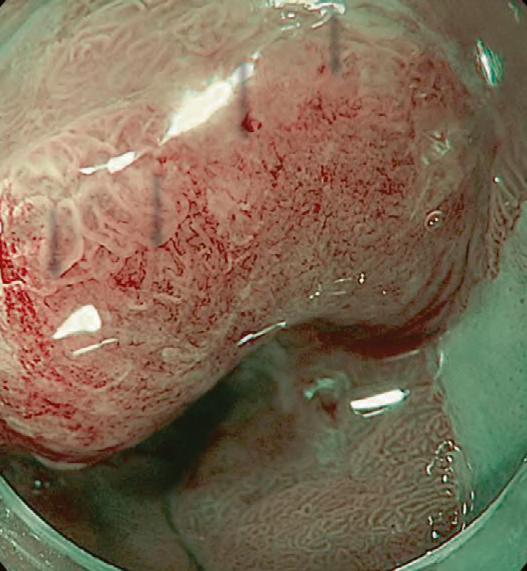

The LASEREO system (FUJIFILM Co., Tokyo, Japan) based on laser endoscopy was developed for advanced IEE, including WLI, BLI, and LCI. LCI using short-wavelength narrow band laser light combined with white laser light is a new technique that enhances differences in red coloration through digital processing [2]. This enables LCI to visualize red lesions better by enhancing their intensity relative to whitish lesions, which appear whiter. Recently, a controlled, multicenter trial with randomization using minimization has reported that LCI is more effective than WLI for detecting neoplastic lesions in the pharynx, esophagus, and stomach [3].

RDI is a type of novel IEE technology included in the EVIS X1 system launched by Olympus Co. in 2020. It is an imaging technique that enhances the contrast of deep tissue and blood vessels [4]. RDI has been reported to be useful for not only its initial development purpose, i.e., endoscopic hemostasis, but also other advanced interventions and even evaluation of inflammation activity. On the other hand, TXI developed by Olympus Co. is designed to enhance three image factors in WLI—texture, brightness, and color—to clearly define subtle tissue differences [5]. TXI is an innovative IEE that facilitates the adjustment of brightness and emphasizes surface irregularities and color differences in endoscopic images. As further data are accumulated, these new IEE technologies are expected to make a significant contribution to clinical practice.