Background

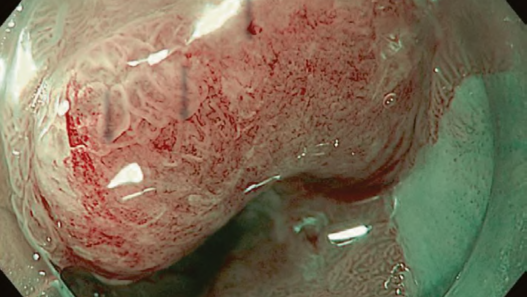

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a metaplastic alteration of the normal esophagus epithelium, predisposing to the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), of which the 5-year overall survival rate is a dismal 17%. International guidelines have recommended endoscopic surveillance for patients with BE to detect early dysplasia. Endoscopic surveillance is typically performed with high-definition white light imaging (WLI) with quadrantic biopsies taken as per the Seattle protocol. However, early Barrett’s dysplasia are easily missed due to subtle mucosal change.

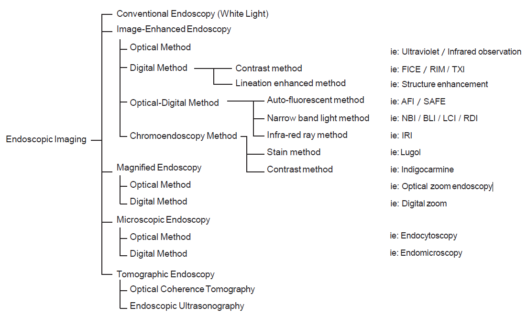

To enhance the accuracy of BE surveillance, narrowband imaging (NBI), along with other advanced imaging tools, is commonly employed in clinical practice. NBI enables improved visualization of both mucosal and vascular patterns within the BE segment, thereby enhancing the detection of dysplasia. Several classification systems, including the Kansas Classification, Amsterdam Classification, Nottingham Classification, and Asia Pacific Barrett’s Consortium Classification, have been developed to predict high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma based on mucosal characteristics. However, these classifications originated from single-center studies, and subsequent validation studies have indicated less than optimal accuracy and interobserver/intraobserver agreements. Given the challenges in detecting dysplasia within Barrett’s esophagus, an accurate and reproducible classification system is essential.

BING Classification

The Barrett’s International NBI Group (BING) was convened to develop and validate a prospective, consensus-driven NBI classification system that can be used to predict the presence or absence of dysplasia in BE. The BING working group is composed of NBI experts from the United States, Europe and Japan, who evaluated 60 high-quality NBI images of non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (NDBE), high- grade dysplasia (HGD), and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), to develop the BING classification.

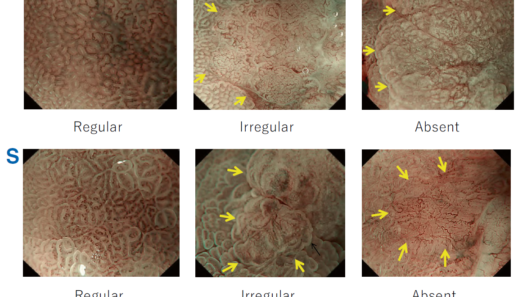

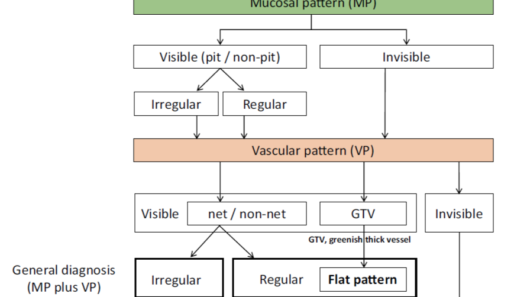

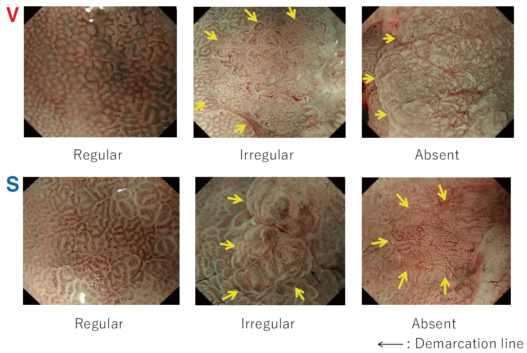

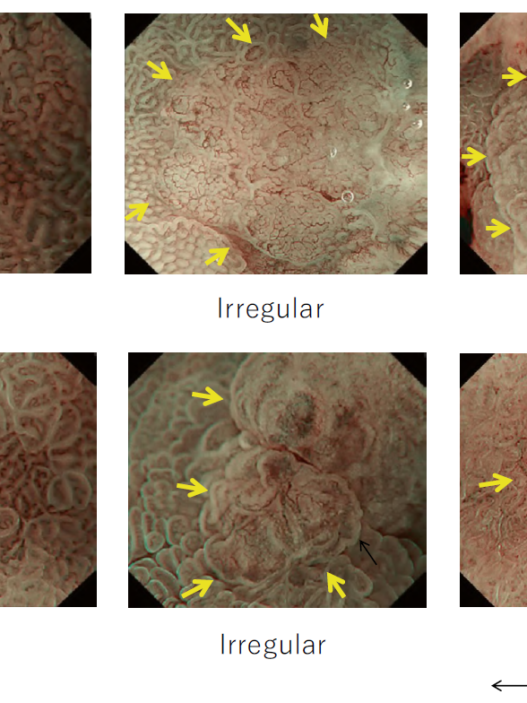

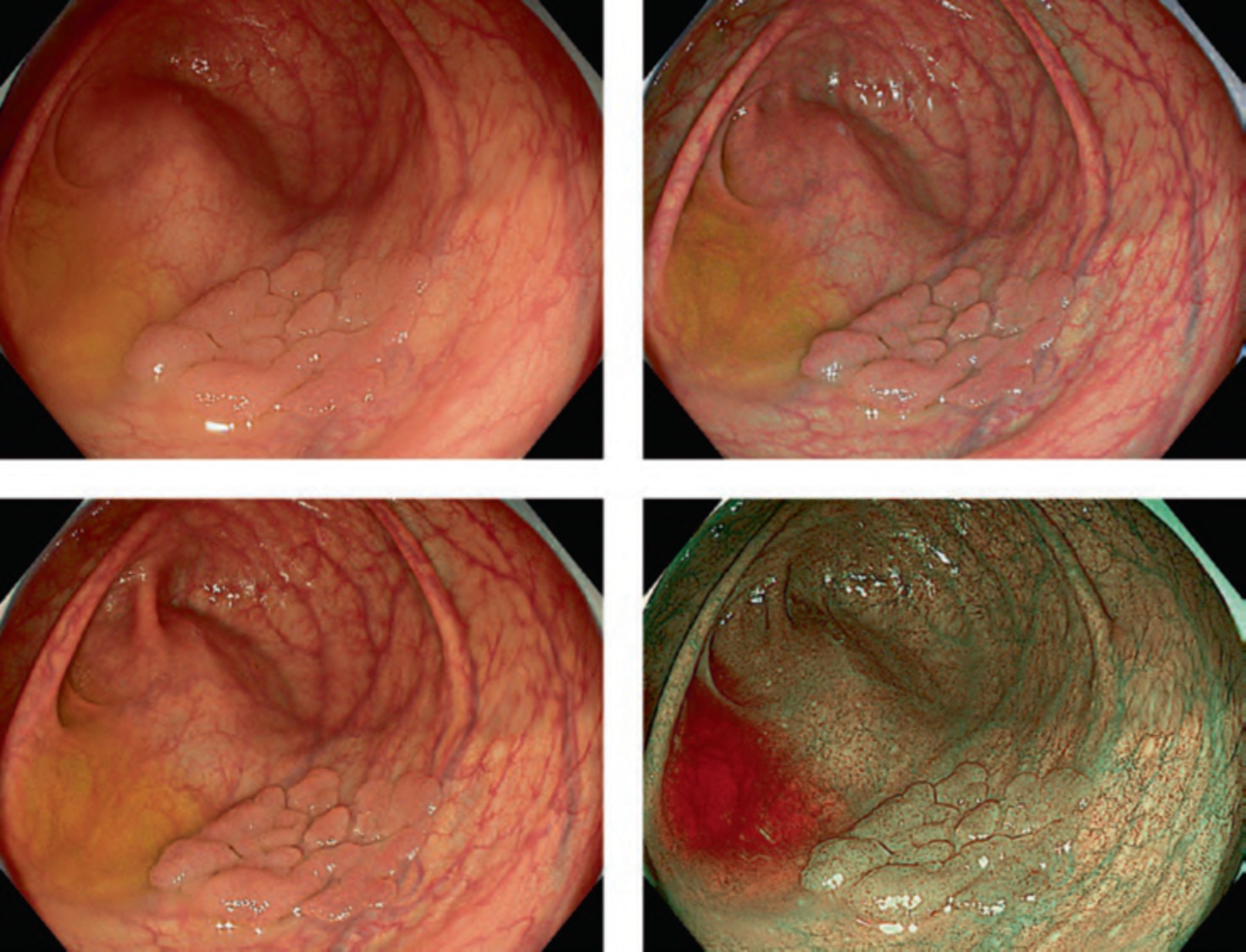

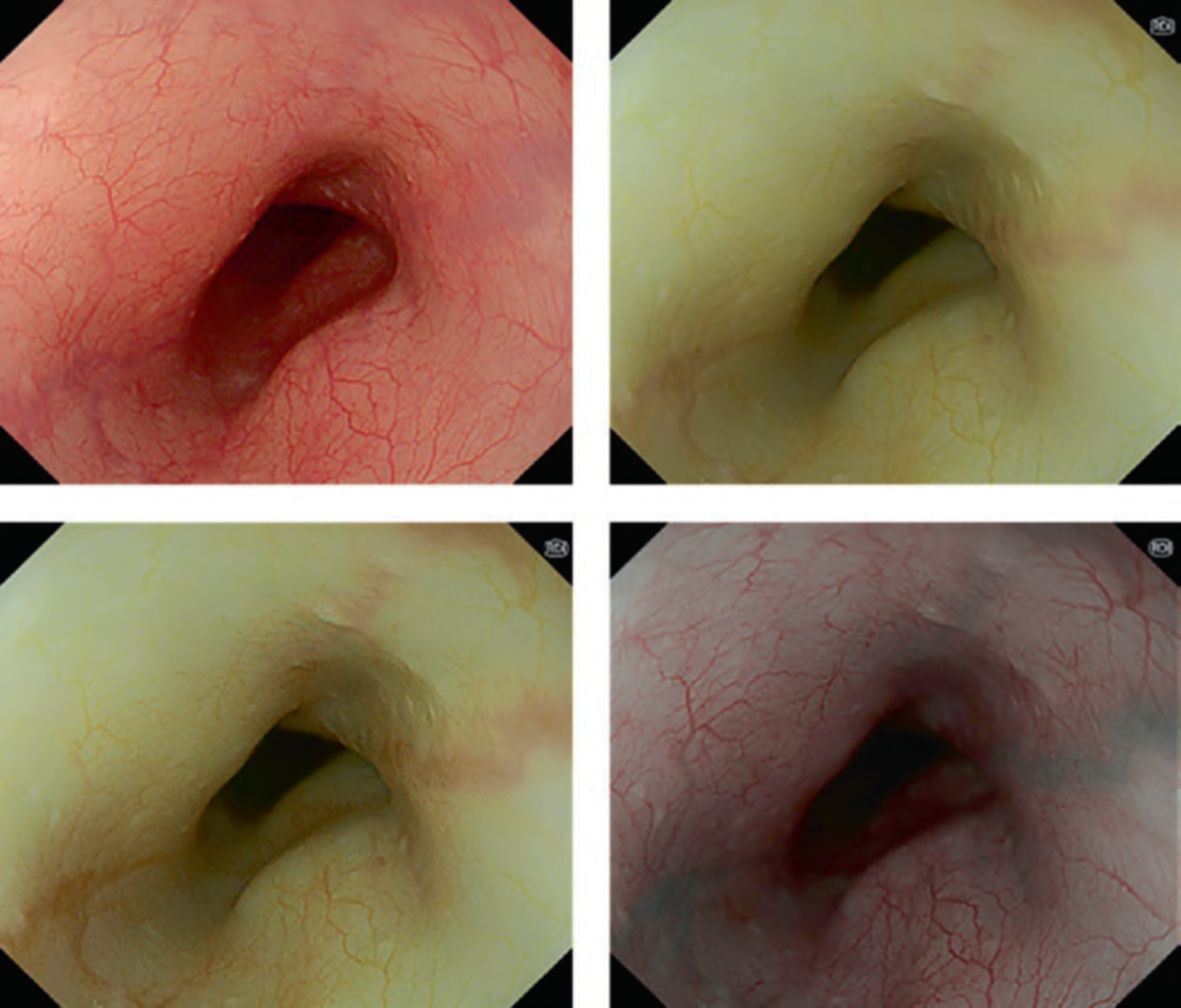

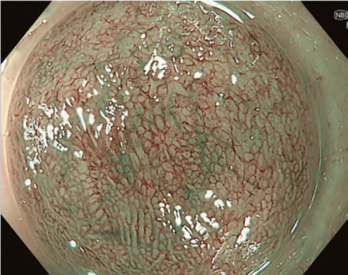

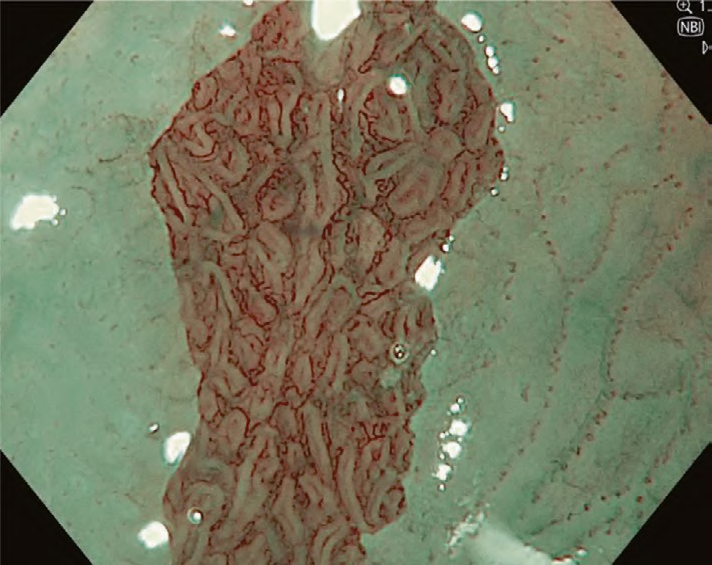

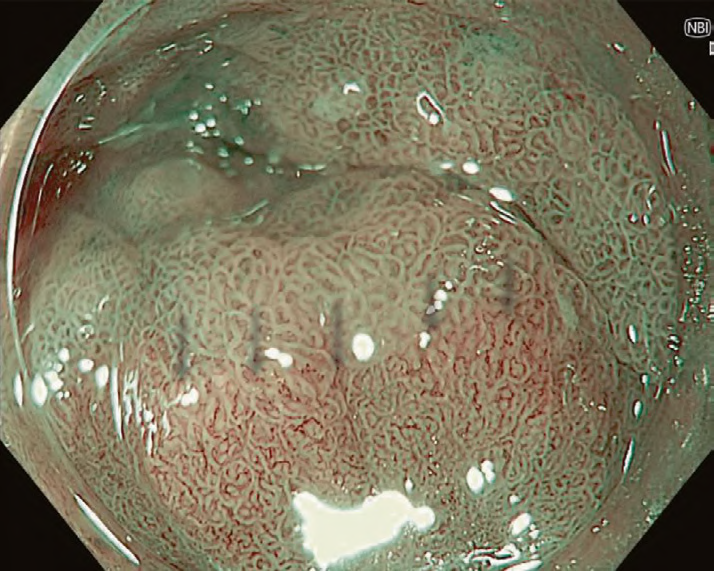

Mucosal and vascular patterns in each NBI image were classified as “regular” or “irregular” based on characteristics agreed upon by the working group (Table 1). Regular mucosal patterns were marked by circular, ridged/villous, or tubular patterns, and irregular mucosa was marked by absent or irregular surface patterns (Fig. 1a, b). Regular vascular patterns were defined by blood vessels situated regularly along or between mucosal ridges and/or those showing normal, long branching patterns; irregular vascular patterns were marked by focally or diffusely distributed vessels not following the normal architecture of the mucosa (Fig. 1c, d). Images not readily identified as regular or irregular were deemed uncertain.

The BING classification was able to detect cases of dysplasia with 85% accuracy, 80% sensitivity, 88% specificity, 81% positive predictive value, and 88% negative predictive value.

| Morphological characteristics | Classification | ||

| Mucosal pattern | |||

| Circular, ridged/villous, or tubular patterns | Regular | ||

| Absent or irregular patterns | Irregular | ||

| Vascular pattern | |||

| Blood vessels situated regularly along or between mucosal ridges and/or those showing normal, long, branching patterns | Regular | ||

| Focally or diffusely distributed vessels not following the normal architecture of the mucosa | Irregular | ||

Nonetheless, the BING classification is not without its limitations. Similar to earlier classification methods, there is notable interobserver variation in agreement among endoscopists (with a Cohen’s value of 0.681). Notably, this classification framework does not encompass low-grade dysplasia or cases of indeterminate dysplasia. Furthermore, the assessment of sub-squamous dysplasia remains elusive.

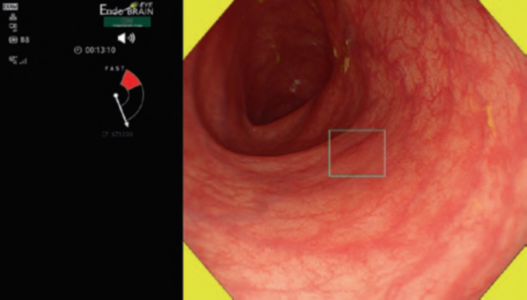

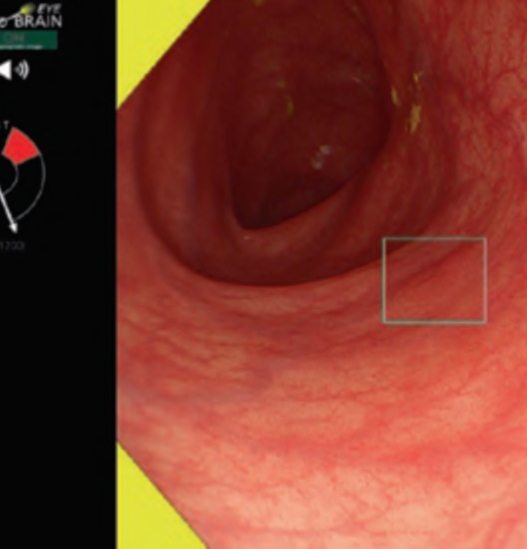

In the foreseeable future, Artificial Intelligence (AI) will have a significant role in Barrett’s surveillance. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that AI has the capacity to enhance early Barrett’s dysplasia detection, achieving an overall accuracy of 94% (95% CI: 0.92–0.96), along with a combined sensitivity of 90.3% (95% CI: 87.1–92.7%) and specificity of 84.4% (95% CI: 80.2–87.9%). Moreover, AI holds the potential to reduce interobserver variation in agreement within clinical practice.

Conclusion

In summary, the BING classification remains an important tool to aid endoscopists in Barrett’s surveillance, assisting in identifying the presence of high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma based on the mucosal and vascular patterns within the Barrett’s esophagus.